Sea, rock and ice

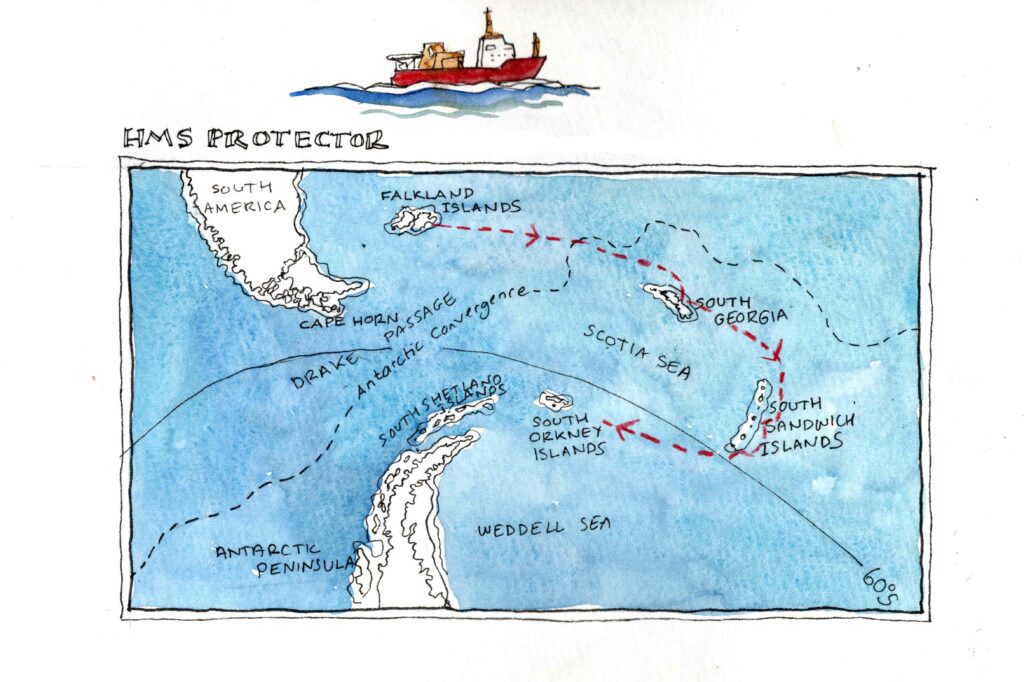

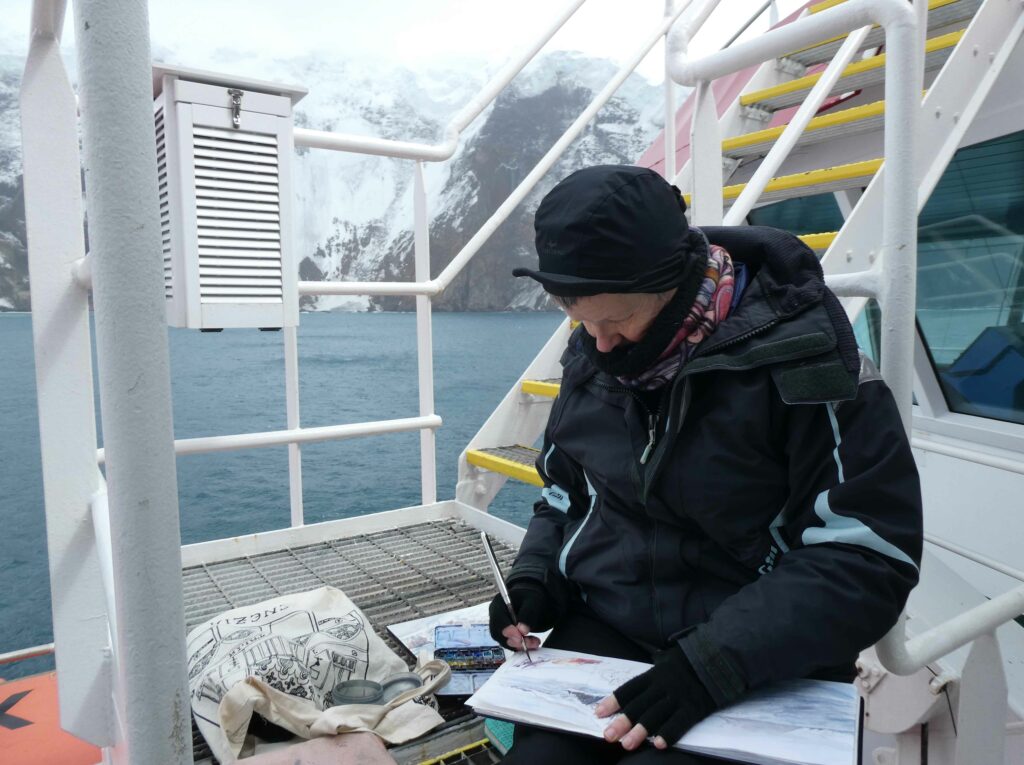

More from the sketchbook diary of a wandering artist – my travels on board HMS Protector as Artist in Residence for Friends of Scott Polar Research Institute

Pause for a moment and look at a world map. Let your eyes travel south, away from the busy squabbling human places, and follow the mountains that form the spine of South America. Where the land ends and the Southern Ocean begins, they form a chain of islands that curve eastwards and back round again to the Antarctic peninsula. On one side of this mountainous ridge is the Pacific plate, to the other the Atlantic; geologically the earth’s crust splits here and it forms part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, a volcanic zone around the ocean where the continental plates meet.

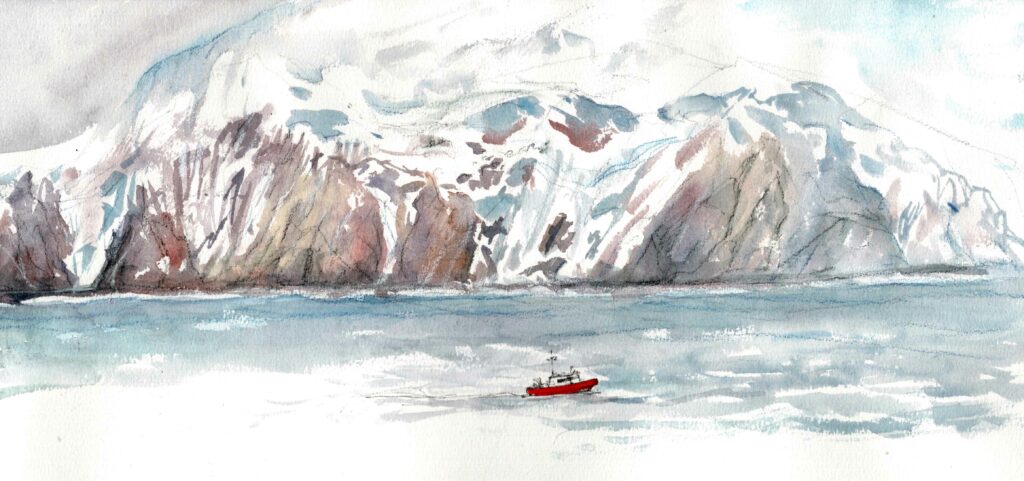

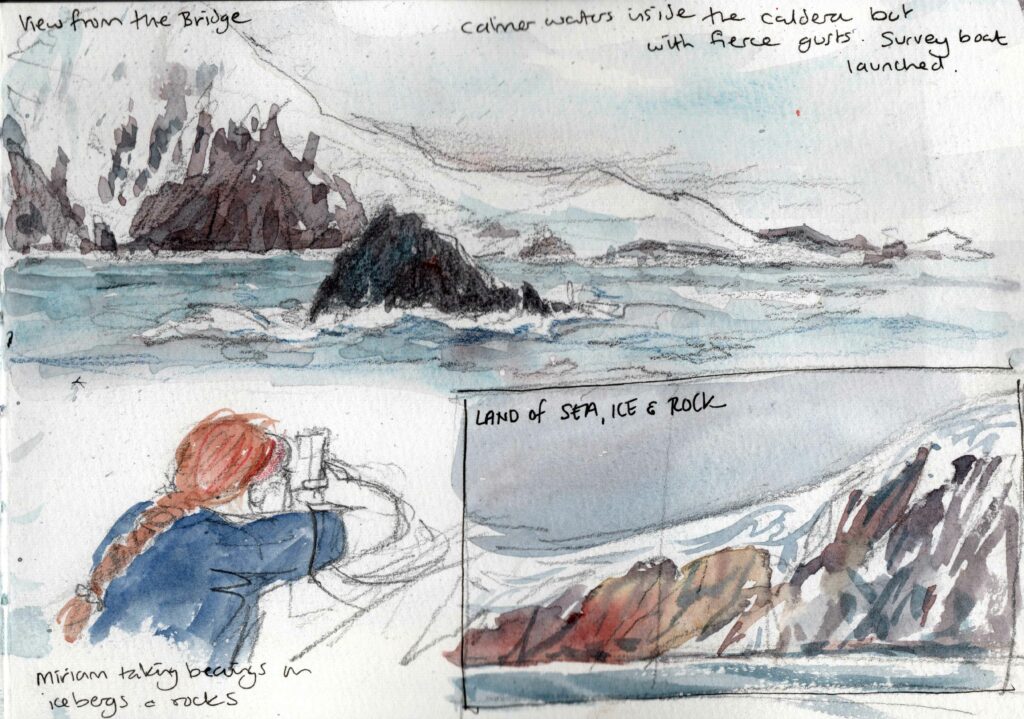

On the easternmost edge of this volcanic ridge are the South Sandwich Islands. They rise steep-sided out of the sea, glaciers and shrieking wind spilling down the face of the dark rock. Like South Georgia, the islands are a British territory, discovered by Cook in 1775, but nobody lives in this land of wind, rock and ice. It’s home to penguins, snow petrels and other birds who thrive on the rich southern seas and seem to care little for the cold. Looking up at those uncompromising steep sided mountains and glaciers, the idea that anyone can own such wild places as these in the first place seems somewhat absurd.

Cook was unimpressed when he first sighted the islands, which he named after the Earl of Sandwich. Disappointed that they were just small islands and not the southern continent that he so hoped to find, he decided not to run the risk of exploring or surveying them too closely:

‘It would have been rashness in me to have risked all which had been done in the Voyage, in finding out and exploaring a Coast which when done would have answered no end whatever, or been of the least use either to Navigation or Geography or indeed any other Science’

Nearly 250 years later, HMS Protector was surveying in comfort, tracking a course parallel to the coast whilst sensors on the hull sent data back to the computers on the bridge for the hydrographers to make a thorough map of the sea bed, bringing the maritime charts up to date and filling in the gaps. A day of surveying meant alternating periods of calm and rough conditions; calm when the ship cruised parallel to the coastline with wind and waves behind her, then suddenly rougher as she turned to track a parallel course the other way, against the elements. In the galley, non-slip mats stopped our meals sliding off the table and walking to the table with your plate of food required some care.

Two attempts to go ashore were both cancelled as there was too much swell to land safely. In Thule, the southernmost island, we got as far as a wet and exhilarating ride in the zodiac looking for a break in the surf before the helmsman judged it was unsafe to land and we headed back to the ship. In survival suits, lifejackets and helmets we stayed dry enough to cope with the icy wind and enjoy the close up view of this wild place where humans do not belong.

Captain Cook was on my mind during that wet and windy ride. Nearly 250 years ago the Resolution would probably have been the first ship in this bay, created from the caldera of an old volcano which is now Thule Island and Cook Island. The crew of Resolution had no engine, no fast RIBS with outboard engines, no lifejackets, survival suits, no satellites to locate them, no radar to warn of icebergs and no charts to guide them. Surveying was a painstaking process of taking continuous sextant readings and compass bearings on landmarks along with measuring the depth of water with a lead line. The skills needed to manoeuvre a three-masted sailing ship in this rock strewn wilderness are hard to imagine.

The video is my attempt to show what I was sketching and how, so apologies for camera wobble and poor sound quality!

I wondered about Captain Cook’s wife, Elizabeth, waiting at home whilst he was away for years at a time. Out of 17 years of marriage, he was home for a total of four years. She bore six children, and survived all of them – some died in infancy, one drowned at sea at the age of 16, and only one made it to adulthood. She must have coped alone with so much birth and death, and clearly had as much fortitude in her own way as her husband.

I am grateful to be alive in the 21st century, with all its woes, and not the 18th!

Cook never knew how close he came to discovering Antarctica. He crossed the Antarctic Circle three times in all, and in 1773 reached as far as 71 degrees.

“I was now tired of these high Southern Latitudes where nothing was to be found but ice and thick fogs.

If he had turned south further west he would have found the Antarctic peninsula, which extends as far as around 63 degrees latitude. He concluded:

‘I had now made the circuit of the Southern Ocean in a high Latitude and traversed it in such a manner as to leave not the least room for the Possibility of there being a continent, unless near the Pole and out of reach of Navigation; by twice visiting the Pacific Tropical Sea, I had not only settled the situation of some old discoveries but made there many new ones and left, I conceive, very little more to be done even in that part.

Brilliant blog Claudia! Loved the descriptions and the connections to Cook. Loved the photo of you too, in the survival suit. Such a small face in that macho helmet, you look a little fragile, which, of course, is far from the truth! xx

Love this Claudia.. your film brought back so many memories of my trip many years ago on RFA Diligence to South Georgia. What a privilege to experience those Southern waters. Keep doing what you’re doing Claudia – you are an inspiration. Xx

Yet another great bedtime read Claudia.

Love this, having once had the pleasure of visiting South Georgia and the Sandwich Islands as a teenager back in ‘95 on the HMS Diligence and never being able to forget the magic of the area, it is always a pleasure to hear about others journeys to this incredible part of our world.

Keep up the great work and hope you get to enjoy many more adventures